When the new Eagle finally hit the newsstands in March 1982, it was with an exciting free! gift – the Space Spinner! That’s a frisbee to you and me. Printed on high-quality paper, it was a glossy product, containing 2 traditional art strips and 4 photo strips.

The lead item was Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future, with fully painted colour artwork by Gerry Embleton. Episode 1 was written by Barrie Tomlinson himself, and titled ‘Return of the Mekon’ – an epic storyline that would last some 18 months. Later episodes were written by John Wagner and Pat Mills. Wagner and Mills no longer wrote together, which means that episodes 2 to 18, credited to Wagner & Mills were actually written by Wagner alone, while later episodes credited to Mills & Wagner were solely written by Mills. They maintained strong continuity with the first episode, in which the Mekon suffers his final defeat, and is sentenced to be imprisoned in space forever. Escaping 200 years later, he returns to Earth, only to find a grave which states that Dan Dare died in 1950. This mystery is left unresolved while the Mekon conquers the Earth, and then Dare’s great grandson, also called Dan Dare, returns from a mission to deep space and finds the Earth already under Treen subjugation.

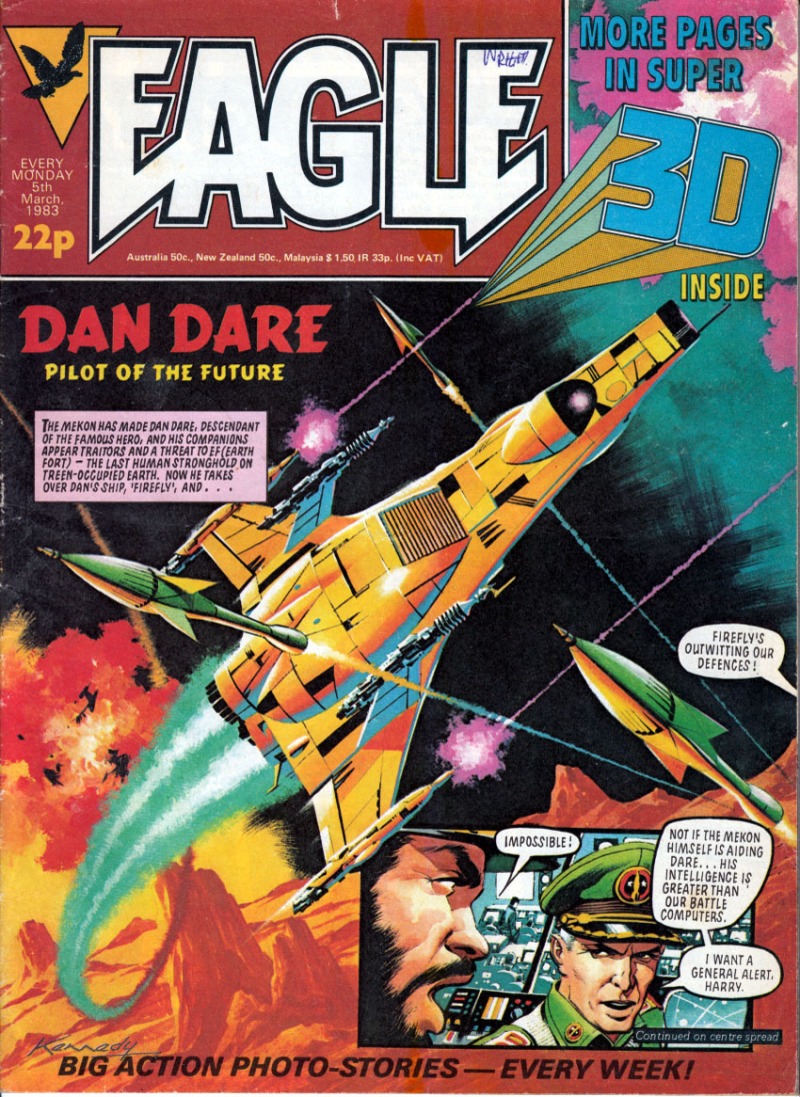

Embleton was best known for his work on TV Century 21 in the 1960s, and although he produces some beautiful art for Dan Dare, his style was perhaps felt to be a little old-fashioned. When Mills takes over the scripting from issue 19, the artist becomes Ian Kennedy. Kennedy is one of my favourite artists from this period, and he does not disappoint, producing some amazing work over the next year or so. The entire look of the strip changes in his hands. While Embleton’s Dare closely resembles the original, under Kennedy, he becomes inexplicably blond, only retaining the freaky eyebrows. All the other characters also change or mutate over time, with Mills apparently unhappy about the direction the strip had taken under Wagner, and moving things in a different direction entirely. What had been under Wagner a series of slightly strange, humorous vignettes begins to head in a more serious direction.

The only other art strip was The Tower King, by Alan Hebden, with some fantastic black and white art by Ortiz. Set in a post-apocalyptic world, where electricity has stopped working, the titular tower king is Mick Tempest, who has taken over the Tower of London, and now uses its walls to defend his people from the freaks and troglodytes who now inhabit the world. Good job he already had the cool name – must have come in handy in that eventuality. This strip is well-remembered by those who read it as kids, but does not reward an adult reading. (Which is the only way I’ve read it. I never got the Eagle at this time, I was still reading the sports comic Tiger – which I mostly hated. More on that, later). Most of what Tempest does is so stupid and random that it should just get him killed. How he’s getting enough food for his people in central London is never addressed, nor is how significant parts of humanity have de-evolved in the few years since the electricity was switched off. It seems as if Hebden’s been given a concept that he doesn’t quite know what to do with. It all looks great, though.

What of the photo strips? Well, first and foremost is Doomlord, written by Alan Grant. Grant was at this time writing with John Wagner. Wagner was not credited on the Doomlord strips (except briefly during Doomlord III under his pen name of “T.B. Grover”), but it seems likely that he also had a hand in most, if not all, of the scripts.

This first Doomlord story ran for 13 weeks, and starred Servitor Doomlord from the planet Nox, who comes to Earth on a mysterious mission. Reporter Howard Harvey spots his spaceship landing, and spends the rest of the tale obsessively chasing the alien, trying to prove that it is him behind the disappearances of top scientists, politicians and generals. Harvey’s new office is clearly represented by Kings Reach Tower – where Eagle (and the other IPC titles) was published from! The interiors are almost certainly shot in the Eagle editorial offices, and staff at the time could probably recognise themselves in the background. Talk about money-saving. As a character, Harvey seems remarkably dedicated to his goal, at one point getting a Concorde to New York in order to catch Doomlord at the UN. Quite an expense on a reporter’s wage!

Doomlord was both distinctive and suited to the photo format, since he could be played by anyone in the skeletal, grinning rubber mask that represented his head – apparently bought from a local joke shop. The character would capture humans, drain all their knowledge (an act in itself which was lethal) then disintegrate them with his energiser ring, and take on their likeness. It is only while in human form that he is vulnerable. Even then, when Harvey shoots him, he is able to scratch another character before he dies, and slowly takes over his body, finally turning back into Doomlord.

Doomlord’s mission becomes apparent when he reveals he is on Earth to judge humanity, and decide whether they deserve annihilation – and he isn’t very impressed with what he sees. In a grim moral for a rather grim story, Harvey comes to agree with the alien: “Mankind has gone wrong! Maybe in the end we will destroy ourselves! But that destruction will not be carried out with your hands!” – all quite typical of Grant’s writing, it must be said. Rest assured that Harvey defeats Doomlord, but only at the expense of both their lives.

Compared with Doomlord, the other photo strips had rather less impact. One was an anthology horror strip call The Collector, in which the titular character shows us an item from his collection, which then leads into a rather grim story associated with it. This strip shows the limitations of the photo format, exemplified in episode 1 ‘Eye of the Fish’ as the Collector himself always appears in artwork (by Pat Wright), then the story unfolds in photos, becoming an uncomfortable mixture of photos and artwork (in this case by Robin Smith) when aliens turn up and capture the human characters on their flying saucer. The photo format always strongly limited the stories you could tell, and the end result was often visually unexciting.

Two of the later Collector stories, ‘Trash!’ in issue 3 and ‘Profits of Doom’ in issue 12, were by comics legend and Watchmen creator Alan Moore – apparently the only time he ever worked for Eagle. That said, he probably doesn’t add these tales to his CV any more, limited by the format, neither is particularly remarkable.

You’ll have gathered by now that I’m not a huge fan of the photo strip format, but it could be effective. Readers at the time often felt that the photographed Doomlord stories were more scary than what came later, as something about the format gave an eerie atmosphere. With The Collector, the most effective story was probably ‘Devil Doll’ in issue 9. This story about a man using little plasticine voodoo dolls comes to a genuinely creepy conclusion which is only enhanced by seeing it in photo form.

Issues 1-11 also contained Sgt. Streetwise, in which a policeman called Wise who works the street (Streetwise – geddit? Oh, suit yourself) tracks down mostly petty criminals using his street smarts and range of disguises. It’s perhaps unfortunate that Wise himself is played by a young man who looks more like an underwear model than a policeman, and stretches our credibility beyond breaking point. It’s also unclear why normal police work would be unable to pick up the mostly purse snatchers and muggers he arrests each week. In fact, he doesn’t even arrest them, usually sloping off to let the boys in blue take the credit, rather than ‘break his cover’. Yawn.

The final strip was Thunderbolt and Smokey, and could not be more inconsequential. It was obviously felt that there needed to be a sports strip, and so the reliable Tom Tully was brought in to write something. Colin ‘Thunderbolt’ Dexter plays football for Dedfield school as the only good player in a team so bad that the sports teacher takes them out of the school league because he can’t be bothered any more. Disgruntled by this, Thunderbolt decides to rebuild the team, with the help of ‘Smokey’ Beckles, a good player from another school, and enter them into the Collyer Cup. They have to win the cup! Yeah! What?

The problem with this strip is that the stakes are so low, that it’s impossible to care what happens. We keep getting told that Dedfield school is more focused on academic success, which as a fuddy-duddy adult, sounds about right to me. None of the characters care, except Thunderbolt, who has a football monomania that’s a bit scary. Even Thunderbolt admits he’s a bit mental for being so focused on the school’s football reputation. The rest of the kids don’t care. The adults certainly don’t care. Even the writer doesn’t care – as will become apparent.

Using the school-age cast has some advantages – the same faces keep coming back for 27 epic weeks of photo story – but also disadvantages as the acting is uniformly terrible. The poses are static and wooden, and the footballing sequences all fail. Between matches, Thunderbolt battles his team through a series of extraordinary difficulties which reach their hysterical peak when the school bully knocks him unconscious (!), vandalises the sports teacher’s car, and frames Thunderbolt by leaving him stretched across the bonnet with a screwdriver in his hand.

So do they win the cup in the end? Spoiler alert: no they don’t. They go into the last match over-confident and after several episodes of tension… lose. Thunderbolt and Smokey wander off into the sunset pondering what sport to fixate over next, and the readership goes “huh? what was the point of all that?”

In issue 12, Streetwise was replaced by Joe Soap, a superior photo strip by Grant and Wagner, about a private detective call Joe ‘Soap’ Soper. This was a humour story, with first-person captions written in the usual sub-Chandleresque patter of this genre wherein Soper describes the daft situations he finds himself in. The humour is perhaps an attempt by Wagner and Grant to find a new way of tackling the limitations of the photo strip, and Joe himself is played by an actor with a very characterful face – somehow, he starts every episode looking like he’s already been punched several times. The scripts are very good, but the somewhat murky photography still seems to undercut and undermine the humour.

In issue 14, the first run of Doomlord is replaced by Saddle Tramp, a photo strip ambitiously set in the wild west. Trampas is a bounty hunter, who ends up carrying his possessions around in a saddle (geddit???), since his horses have a nasty habit of getting killed from under him. To get some realistic backgrounds, the photographer does seem to have used a ‘Western’ town – possibly Laredo in Kent – for many sequences. The costumes are mostly not too bad, although the background performers seem to be the same 3 or 4 cosplayers from episode to episode. The biggest problem comes whenever Trampas is required to leave town and start crossing the desert, the entirety of which appears to be represented by one small sandpit with a telegraph pole and a puddle at the bottom. Colour me unconvinced.

The comic was rounded out by some funnies from ‘Ernie the Eagle’, regular columns from the likes of DJ Mike Read (who mostly talks about tennis and the latest celebrities he’s met), and also ‘Glamourous Teacher’ – slightly disturbing to modern eyes – in which young boys are encouraged to send in photos of their hottest female teachers for publication. Of which the best that can be said is that it’s not quite as bad as it sounds.