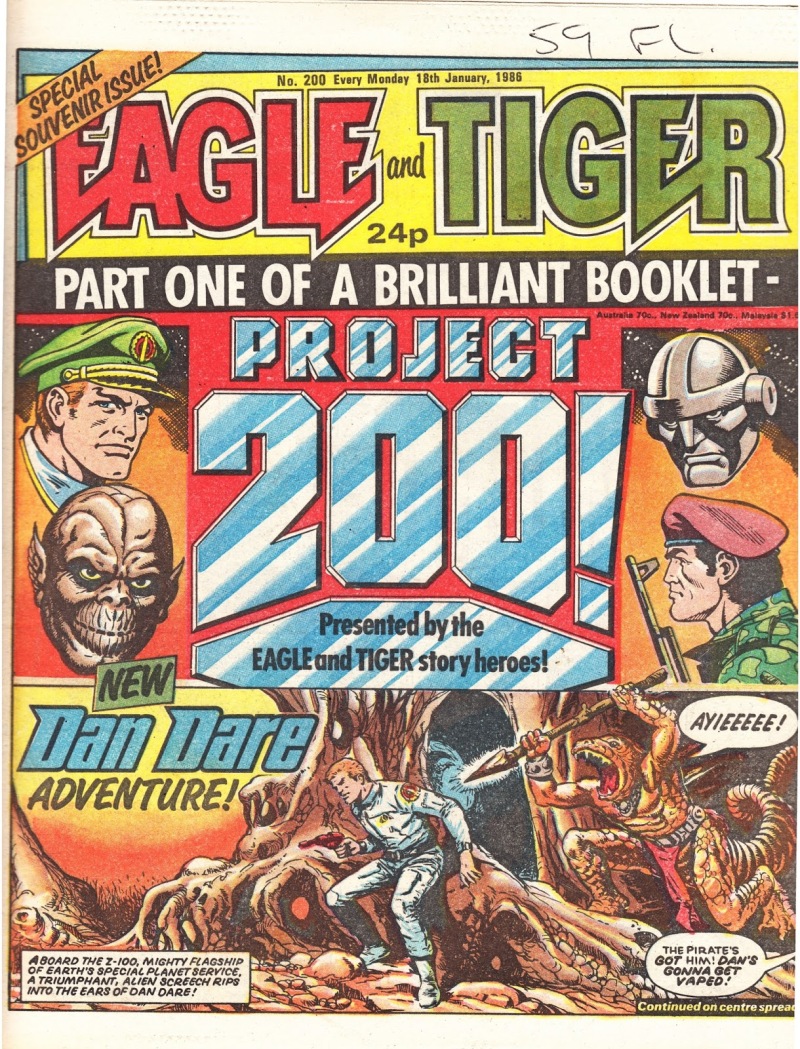

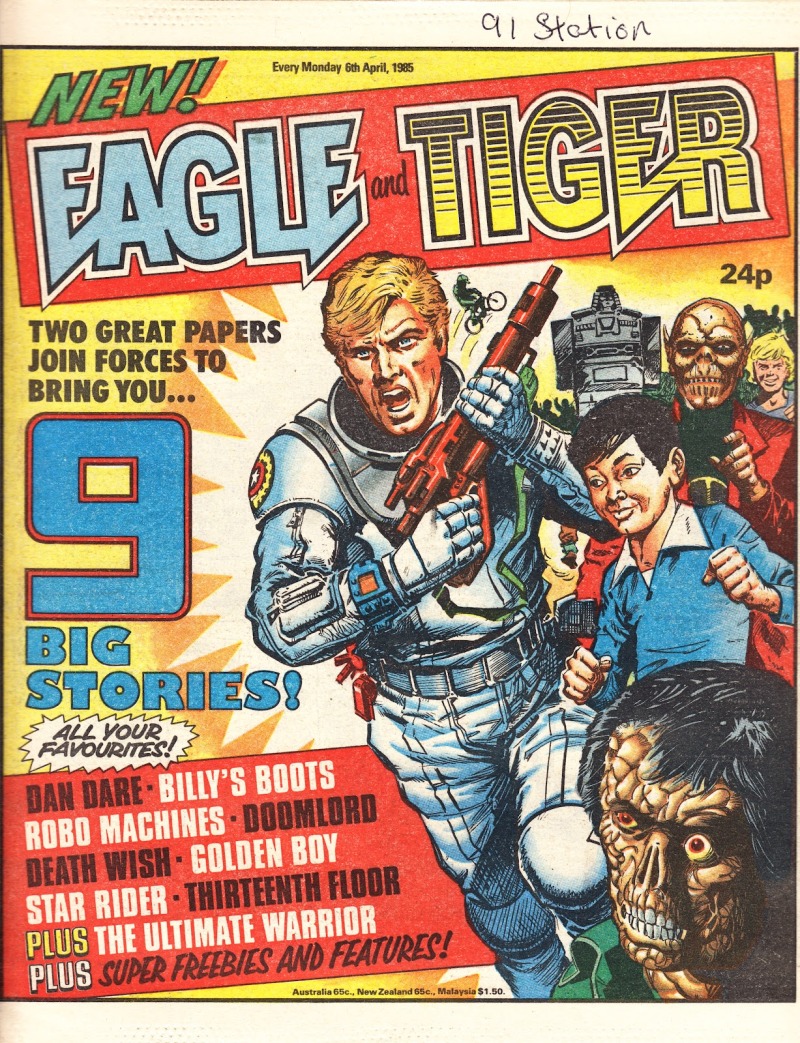

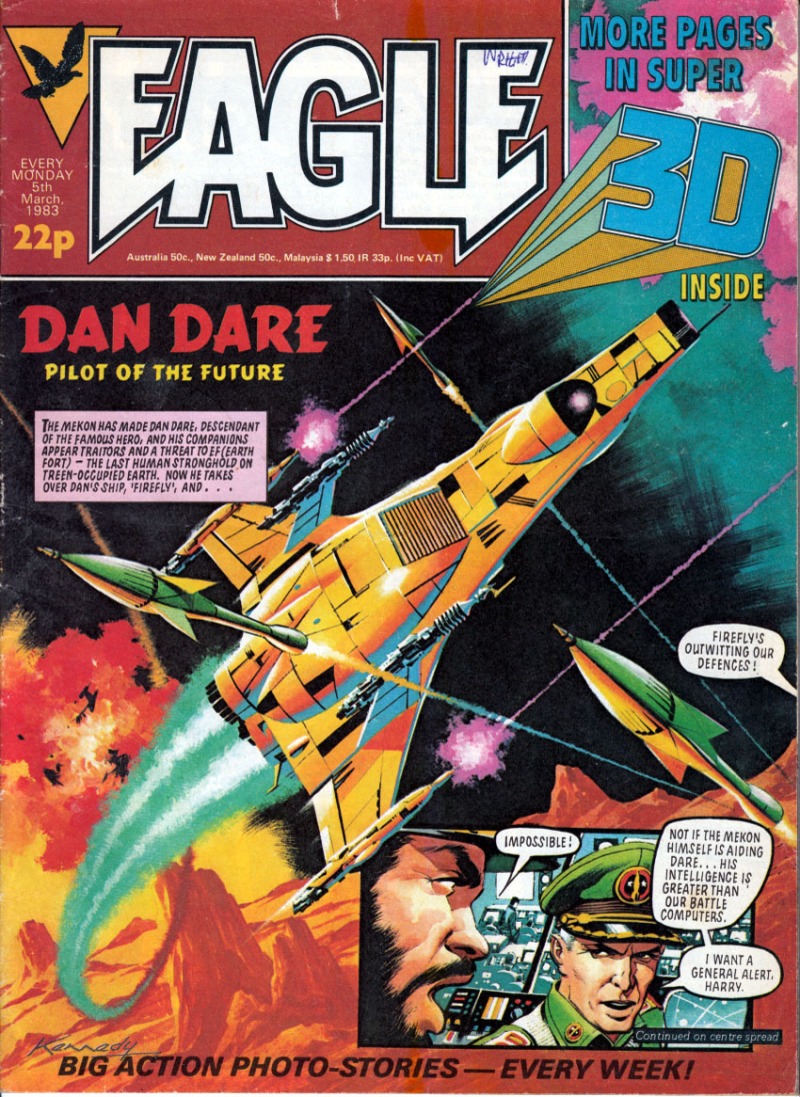

By the mid-to-late 80s, computers were changing the economics of publishing. As colour and other printing processes got cheaper, Eagle finally threw off the ear of inky newsprint, and with issue 259 (7th March 1987) re-launched with a new look. It’s an indication of how important to IPC Eagle was, that 2000AD would not do the same thing for another couple of months.

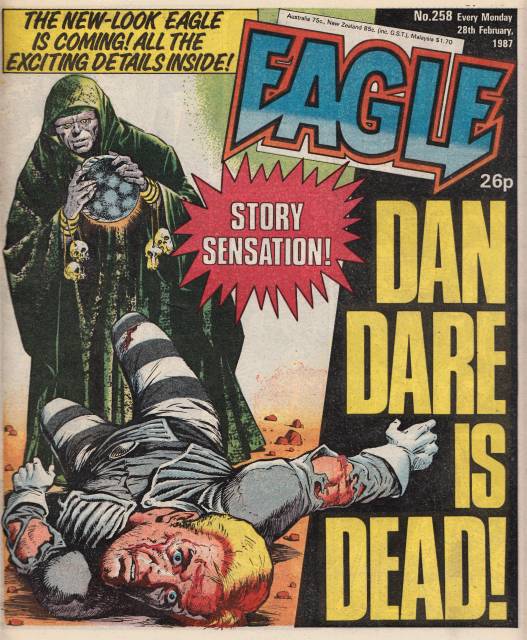

The most obvious beneficiary of the change was Dan Dare, for which Carlos Cruz could now provide fully painted colour art for the first time since the days of Ian Kennedy and Pat Mills 4 years earlier. The script was still by Tom Tully, although he went uncredited for a few issues. In fact, it was business as usual, except for the fact that Dan Dare was dead. This is soon solved, as the Mysterons – sorry, Mythereons – turn up to bring him back to life to ‘balance’ a cosmos which needs a Dan to oppose the evil of the Mekon. Quite why they should think that now is a bit of a mystery, as the Mekon has been trapped in time since their last encounter (see “Eagle issues 209-229”), and turns out to be causing trouble in London in 1987.

All of this is, of course, an excuse for a bit of a re-format, as Dare is brought back from the dead somehow angrier and more aggressive than before – a move bound to antagonise purists. Most of the old characters like simply Pinkerton disappear, while Digby – now confined to a wheelchair – only appears in a few episodes.

After some angry shouting, Dare follows the Mekon to 1987, but the green dome-head escapes back to the 23rd century with some McGuffinaneum rock (I may have just made that up) he’s stolen from the British museum. Dare has to return empty-handed apart from Zapper Lawrence, a twentieth century teenager who implausibly turns out to be brilliant at the weapon systems of the future. In concept, Zapper resembles Flamer Spry from the original strips, but with the extra wish-fulfilment frisson that he’s from the present day. Dan now goes about putting together an elite team called Dare’s Eagles. Unfortunately, he goes for a rather unsophisticated recruitment policy, which simply consists of wandering around, and hiring whoever he happens to bump into. Ultimately, this ‘team’ consists of Zapper, a mutated blue Treen called Tremloc and coolest of all, walking cliché Apsilon Stelth, an alien knight, dying of a deadly disease, and with his own catchphrase – “Detrimus Krede!”. Later on, they get joined by Velvet O’Neal, a Tully character who had appeared in some previous stories, but who now takes on a larger role, and celebrates by adopting a much tighter jumpsuit. During a lengthy story, they now pursue the Mekon in Dare’s new spaceship – the Britannia Eagle – in an effort to stop him building a mcguffinaneum-based doomsday weapon which will destroy the entire galaxy. For some reason. Unfortunately, Zapper and Tremloc’s main contributions are getting into trouble and hindering the mission. Dare would have been better off asking for CVs and references. Partly as a result of this, the Mekon gets to launch his weapon. Disappointingly, Dare solves this dilemma by shooting it. With his handgun. Having left the Britannia Eagle in a spacesuit for the express purpose of doing this. Sheesh.

Some dodgy plotting aside, Dare had rarely looked better. Unfortunately, the pressure of producing 3-4 pages of fully painted art each week seems to have been a struggle for Cruz. Ian Kennedy steps in for one episode, and Redondo for some others. Towards the end of the Dare’s Eagles plot-line, an episode appears where the two central pages of art are by Cruz, while the back cover appears to be the work of someone else – possibly Redondo again. Clearly something would have to give.

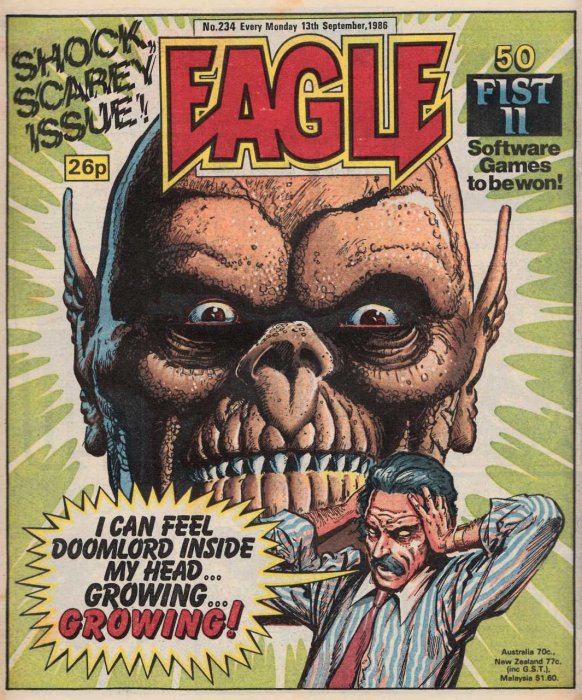

Eagle at this point was still running reprints of old 2000AD strip MACH 1, skipping episodes where necessary so that the storyline would come to an end in time for another revamp after issue 284. It still looked somewhat out-of-place, although as usual, the Pat Mills scripted episodes were often the best thing to appear in any given issue. The comic was also managing to fit in more pages per story, by reducing from 9 weekly strips to 8. This meant that Doomlord was now alternating 3 and 4 pages episodes, allowing some extra sophistication in story-telling. It kicks off the new era in fine style, with ‘Tibor’s Alien Circus’, in which the Souster boys are kidnapped by a weird inter-dimensional circus, and so is Doomlord when he tries to rescue them. The storyline from there is a straightforward series of escape attempts by Vek, but gives artist Eric Bradbury a fine opportunity to demonstrate his skills by creating more weird and wonderful alien creatures. Attempting to return home after defeating Tibor, Vek and the boys are then propelled into another adventure where they visit a version of Earth where Enok defeated his father and created a totalitarian society explicitly based on Orwell’s 1984. The twist (that they’re actually in an alternate dimension) comes surprisingly late in the day, but gives writers Grant and Wagner a chance to really push the concept to its limit. Doomlord had never been better.

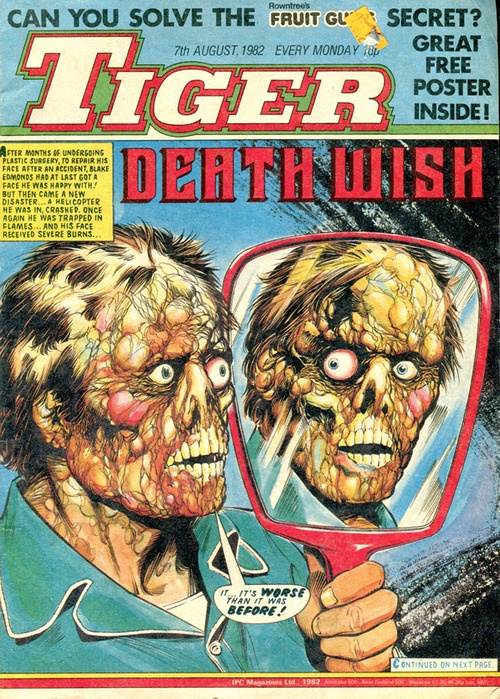

The same cannot be said for Death Wish, which seems to have had its own death wish by this stage. The Blake-meets-supernatural cliches had been almost played-out by now, but was given one last shot in the arm by having him and Suzie meet none other than Dracula himself. In fact, this Dracula turns out to be more Bela Lugosi than Bram Stoker, and it’s hard to imagine that writer Barrie Tomlinson put much research into his storyline. With the help of his assistant Igor, Dracula hypnotises Suzie and gets her to drive his hearse. Blake heads in pursuit, with all the trademark Death Wish action and crashing helicopters (seriously – they crash helicopters in Death Wish like, all of the time), and after a prologue in issue 258, the story gets spun out for another 19 episodes.

After 7 years, Death Wish had now strayed a long way from its original USP of the story about a stunt man who doesn’t care whether he lives or dies. Perhaps recognising this, it was now re-titled (from issue 285) as The Incredible Adventures of Blake Edmonds (a Death Wish story). This somewhat unwieldy moniker appeared 8 episodes into an even longer storyline where, while investigating some spooky goings-on, Blake and Suzie get accidentally shrunk by a mad scientist down to a few inches tall. Not so much incredible as unbelievable, their latest escapades involve being attacked by insects, sucked up by vacuum cleaners and shut inside washing machines. Captured by some extraordinarily unscrupulous locals, they are locked up in a converted dollhouse, due to be exploited for TV fame and fortune. At 28 episodes, this story very much outstays its welcome. Having squeezed every possible incident out of Blake and Suzie being tiny, Tomlinson has them blown up to giant size and attacked by (you guessed it) helicopters which Blake accidentally bats out of the sky. Clearly, this could not go on much longer, and when it rains overnight, Blake and Suzie shrink back to normal size. At no previous point has the story suggested that they’re water-soluble – particularly when they were tiny and got taken up into washing machines or flushed down storm drains. But no, that’s the end. They shrink in the rain – move on. The ideas sump was empty – when the story came to an end in issue 305, so did Death Wish itself. It had been running in various publications since February 1980, and by my reckoning had clocked up over 400 episodes, 147 of them in Eagle. It was the last remaining relic of the Eagle and Tiger days, but in truth, it had been a shadow of its former self for quite some time.

Tomlinson was capable of more than this. Issue 259 also saw the debut of his new strip, Survival, which is probably the most adult strip he ever produced for Eagle. Like the Terry Nation TV series Survivors, it picks up after the human race has been wiped out by a plague. In Survival, the only survivors are a small number of children with a select blood type, and we follow the adventures of Mark Davies as he treks around Britain, looking for food and for someone else who might have survived. One thing Survival gets across is the terrible loneliness of his position, combined with the desperation to find someone – anyone – to talk to. For a long time, his only friend is an elephant which has been released from a local zoo by a dying zookeeper. If the idea of a bond between a boy and an elephant requires us to suspend disbelief, then it is not unique. The story’s biggest problem, is the constant need for action and a cliffhanger every 3 to 4 pages, which Tomlinson provides as efficiently as ever. To this end, elephants aside, animals are Mark’s enemies, as he gets attacked by tigers, dogs, rats, cats, crocodiles and even – at one point – birds. Having largely run out of animals, Tomlinson has Mark and his new friend Karl (after his elephant has taken off, Mark finally meets another boy) menaced by monsters. In a gee-I-wish-I’d-thought-of-this-before moment, the monsters turn out to be adult survivors of the plague, mutated and damaged mentally and physically , as well as being apparently) mute.

Frankly, Tomlinson is definitely – definitely – making this stuff up as he goes along. I remember reading this story in its original form in the late 1980s – taken in weekly instalments Mark’s predicament seemed to play over a very long time. When read in quick succession, the episodes are less effective, as each unlikely action sequence follows hard on the previous one. The artwork is by the ever-reliable Jose Ortiz. Ortiz had provided previous dystopias for Eagle such as The Tower King, but excels here, as he shows Mark ageing over time, and also brilliantly portrays the collapsing human world gradually getting taken over by undergrowth. By issue 284, Mark and Karl have decided to cross the channel, on the unlikely assumption that things will be better in France. On the way, they have a brief, grim encounter which illustrates what Survival did best. They meet an adult, who by remaining isolated on a lighthouse has survived the plague. Unfortunately, his isolation has sent him mad, so that he attacks them and eventually falls off his lighthouse and dies. In the basement, his mate is just a skeleton – the boys are traumatised but carry on. 26 episodes in, Survival was just hitting its stride.

Two more strips also debuted in issue 259. Of these, more successful was probably Comrade Bronski, written by Alan Hebden. I remember being excited at the time, as the art was provided by comics legend Carlos Ezquerra. Ezquerra is not a slow artist, but how he fitted this into his schedule is a mystery to me, as he was still working practically full time drawing Strontium Dog for 2000AD. In fact, Comrade Bronski appeared during the lengthy storyline (‘Bitch’) which introduced the perennially popular Durham Red. Unlike Strontium Dog, Bronski is set in the present day of 1987, in what was (still) Soviet Russia. In the first episode, Bronski is released from the gulag, and asked to set up a new special investigations force (apparently by premier Gorbachev himself) in a rival position to the KGB. It’s a clever scenario, only undermined by the unlikelihood of just how long someone in Bronski’s position could get away with being as arrogant and insubordinate as he is. The other let down is that increasingly often Mike Dorey has to step in to provide the art, until – about 16 episodes in – Ezquerra disappears entirely. Dorey takes over for the final stories, and is a perfectly competent replacement, but for me the strip lost something, and it comes to a close after 23 episodes.

The other new strip was Avenger by “W Steele”. No one was stood up to admit being W Steele, although I strongly suspect that this was also Alan Hebden (see next time for why). Perhaps he didn’t want to admit to writing Avenger (no relation to the Marvel Avengers or to John Steed), as the central concept is, er, a bit right-wing. Physics teacher and keen motorcyclist Paul Cannon witnesses yobs running another car off the road, which then immediately bursts into flame killing all four people inside. Cannon testifies against the yobs in court (they have got “Yobmobile” scrawled across the side of their car, so we know what they’re about), but he is disgusted when they are just sentenced to a £200 fine and two years ban from driving. “They kill four people and walk away laughing!” he thinks. “That may be the judge’s idea of justice – but it’s not mine! Those animals deserve to pay for what they did – and I’m going to make sure that they do!” To this end, he uses his science skills to create a stick capable of giving electric shocks, and creates a clever disguise by having a visor he can pull down from the front of his motorcycle helmet. However, you wouldn’t have to be a genius to recognise him, as his helmet has the same distinctive ‘A’ logo on the front whether he’s in disguise or not. It shouldn’t really come as a surprise that one of Cannon’s pupils, Dave Henderson, is rapidly ‘on’ to him, and when he’s not beating up villains, Cannon spends much of his time trying to convince him otherwise.

Something about this concept never quite clicks, and the subject is a poor fit for artist Mike Western’s realistic style. It doesn’t help that Cannon is violent but never really likeable and so we don’t care what happens to him. Plus his gadgets aren’t exactly Batman. Eagle never really came up with a successful super-hero strip, and Avenger is no exception. Perhaps British writers struggled with the concept (Alan Moore aside). Superheroes always need super-villains, and by the end of the strip, we’ve met Ultra-man, who has created an entire exoskeleton and uses it to rob banks. The story comes to an abrupt end in issue 284 (29 August 1987), with Avenger announcing in a thought bubble that now that he’s defeated Ultra-man, it’s time for him to disappear as well. He’s not wrong.

Story index part 8: 259-284

DOOMLORD Tibor's Alien Carnival, 13 episodes, issues 259-271 (Mar. to May 1987) Story by Alan Grant, art by Eric Bradbury untitled (“Enok's World”), 16 episodes, issues 272-287 (June to Sep. 1987) Story by Alan Grant, art by Eric Bradbury (eps 1-14,16) & Dave De'Antiquis (ep 15) AVENGER Avenger, 26 episodes, issues 259-284 (Mar. to Aug. 1987) Story by W Steele, art by Mike Western SURVIVAL Survival, 47 episodes, issues 259-305 (Mar. 1987 to Jan. 1988) Story by D Horton (Barrie Tomlinson), art by Jose Ortiz DAN DARE, PILOT OF THE FUTURE untitled (“Mekon in 1987”), 9 episodes, issues 259-267 (Mar. to May 1987) Story by uncredited, art by Carlos Cruz untitled (“Dare's Eagles”), 31 episodes, issues 268-298 (May to Dec. 1987) Story by Tom Tully, art by Ian Kennedy (ep 1), Carlos Cruz (eps 2-11,14-31) & Redondo (eps 12-13, 29?) DEATH WISH untitled (“Dracula”), 19 episodes, issues 259-277 (Mar. to July 1987) Story by D Horton (Barrie Tomlinson), art by Eduardo Vanyo The Incredible Adventures of Blake Edmonds, 28 episodes, issues 278-305 (July 1987 to Jan. 1988) Story by D Horton (Barrie Tomlinson), art by Eduardo Vanyo COMRADE BRONSKI Comrade Bronski, 12 episodes, issues 259-270 (Mar. to May 1987) Story by Alan Hebden, art by Carlos Ezquerra (eps 1-4,6,9-10) & Mike Dorey (eps 5,7-8,11-12) untitled (“The Siberian”), 4 episodes, issues 272-275 (June 1987) Story by Alan Hebden, art by Carlos Ezquerra untitled, 7 episodes, issues 277-283 (July to Aug. 1987) Story by Alan Hebden, art by Mike Dorey COMPUTER WARRIOR Express Raider, 8 episodes, issues 259-266 (Mar. to Apr. 1987) Story by B Waddle/D Spence (John Wagner), art by Robin Smith World Games, 6 episodes, issues 267-272 (May to June 1987) Story by B Waddle (John Wagner), art by Robin Smith Ace of Aces, 8 episodes, issues 273-280 (June to Aug. 1987) Story by B Waddle (John Wagner), art by Robin Smith Metrocross, 4 episodes, issues 281-284 (Aug. 1987) Story by B Waddle (John Wagner), art by Robin Smith M.A.C.H.1 untitled (“UFO”), 4 episodes, issues 260-263 (Mar. to Apr. 1987) Story by Pat Mills, art by Freixas untitled (“MACH Woman”), 4 episodes, issues 264-267 (Apr. to May 1987) Story by Alan Hebden, art by Lozano & Canos (eps 1-3) Death Ray, 3 episodes, issues 268-270 (May 1987) Story by Alan Hebden, art by Lozano & Canos MACH Zero, 4 episodes, issues 271-274 (May to June 1987) Story by Steve McManus, art by Ramon Sola untitled (“Return to Sharpe”), issue 275 (June 1987) Story by Roy Preston, art by Montero The Dolphin Tapes, 4 episodes, issues 276-279 (July 1987) Story by Steve McManus/Oniano, art by Redondo (eps 1-2) & Montero (eps 3-4) untitled (“Origins”), issue 280 (Aug. 1987) Story by Nick Landau/Roy Preston, art by Lothano The Final Encounter, 4 episodes, issues 281-284 (Aug. 1987) Story by Pat Mills, art by Montero